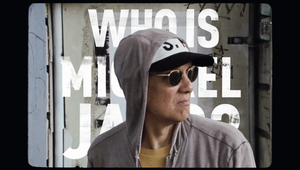

LBB Film Club: Who is Michael Jang?

Who is Michael Jang? A question that many have sought to answer, including Strike Anywhere director, Michael Jacobs, in his latest documentary on the enigmatic commercial and street photographer and Bay Area cult icon, Michael Jang.

A man of many characters and figure of mystique, Michael Jang’s photography started as candid snapshots documenting the life and personalities of his Asian-American family in the ‘70s. Evolving into black and white street photography and portraits of icons including Robin Williams, David Bowie and The Sex Pistols, Jang’s photography was off-the-cuff, humourous and honest – portraying the sense that he was exactly in the right place at the right time.

Despite this, much of Jang’s work sat boxed away until recent years, as he pursued a career as a commercial photographer - documenting everything from Bar Mitzvahs, family portraits and weddings, to pay the bills and fill the fridge.

After sharing a selection of prints with the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2002, Jang’s work became more well known, especially in the Bay Area, but it was the covid-19 pandemic that saw awareness of him and his art rise. Pasting San Francisco neighbourhoods with larger-than-life reproductions of his prints, Jang tackled anti-Asian rhetoric that grew during the period, as well as the closure of museums and galleries – using the street as a canvas instead.

Chronicling Jang’s career through his own photography, testimonials, archival footage and present-day interviews with Michael himself, Michael Jacobs directs a playful yet emotive insight into Jang, offering a lens into the man typically behind the camera. The full film is set to air on PBS in May 2025, but you can take a look at the trailer, and learn more about how the film came to life in the interview below.

LBB> How and when did you first hear about Michael Jang?

Michael> I first met Michael Jang backstage at Popup Magazine (a now-defunct fantastic live show that did not survive the pandemic), where I was presenting a film, and Jang was presenting a series of photographs. His images were incredible. I was also captivated by his wit, charm, and storytelling. I couldn’t believe I had never heard of him or seen any of his work before.

LBB> And what made you want to tell his story, and why was a documentary the right medium to do it?

Michael> The more I discovered about Jang and his body of work, the more curious I became. Once the pandemic hit and Jang began wheat-pasting massive reproductions of his vintage prints across the streets of San Francisco, I had to find out more about him. For me, documentaries are the ultimate vehicle for exploration and discovery, an excuse to satisfy my deep curiosity about the world.

LBB> You speak to members of Michael’s family, as well as his curators and collaborators - how did you go about finding the right people to talk to?

Michael> I quickly found out that people in the know about Michael Jang are extremely passionate about him and his photography. It was also so helpful that his appreciators represented a fantastic cross-section of people. It’s rare to get to film with someone so beloved across fine art, street art, and performance art communities and cultures.

LBB> What was it like working with Michael himself?

Michael> Working with a living artist presents various challenges, especially for someone who’s protective of his brand and has been very cautious about sharing personal information. It's my film, but it's also about Jang’s life and art. It's deeply personal to both of us, but in vastly different ways. It took a lot of trust on both sides and some time to get into a rhythm.

LBB> How did you weave together Michael’s work, archival footage and present-day interviews to craft the narrative in the documentary?

Michael> Big shout to editor Clayton Worfolk, who was tasked with structuring and then being unafraid to break that structure to find the right balance between biography, fine art imagery, and immersive verite.

We experimented with different sequencing to unravel the mystery and mystique behind Jang without giving too much away or assuming this film would be the final word on Michael Jang, which it most certainly is not!

We also had to make difficult choices about what material to include or withhold about somebody’s personal life while still serving the audience. This is always a difficult balance in documentaries, but it proved extremely challenging on this one.

LBB> Did you make use of any interesting filmmaking techniques to bring the film to life?

Michael> Director of Photography Tyler McPherron and I spent months developing a visual language. Our intention was to create a sense of urgency for Michael’s recent street art alongside a historical appreciation for Jang’s still photographs.

We utilised a variety of shooting formats, including 8MM and 16MM film and cell phone captures alongside our A camera (the Sony Venice), to aid transitions in and out of archival and time and place.

Michael’s hero interview frame was shot in colour and direct to camera so the audience could study his face and make eye contact. Whereas we shot the subject interviews in black and white in a square aspect ratio as a nod to Jang’s vintage prints.

LBB> What was the most striking takeaway that you got from the production process?

Michael> This was by far the most collaborative I have ever been with a subject in one of my films. This was uncomfortable for me at first. The idea of sharing various scenes felt like giving away too much control. It took some time for Jang to accept my perspective of his life and the brevity required of the editorial process. But as Jang came to not only understand but appreciate some of the storytelling choices we were making, he became a vital collaborator in sourcing additional material from his archive and fact-checking his own life story.

LBB> What do you hope that audiences learn about Michael after watching the film?

Michael> Something really wonderful about the early release screenings is that the audiences, in some cases for the first time, discover an important American artist whose life and story are unique yet relatable to just about everyone.

LBB> And finally, if you were to do this again, is there anything you’d do differently?

Michael> I rarely watch my films once they're finished, as all I see are mistakes and missed opportunities. It's a curse of sorts that I know a lot of other filmmakers are afflicted with as well.